The list of U.S. big-city police departments under federal scrutiny seems to keep growing: Chicago. Minneapolis. Louisville. Seattle and Phoenix.

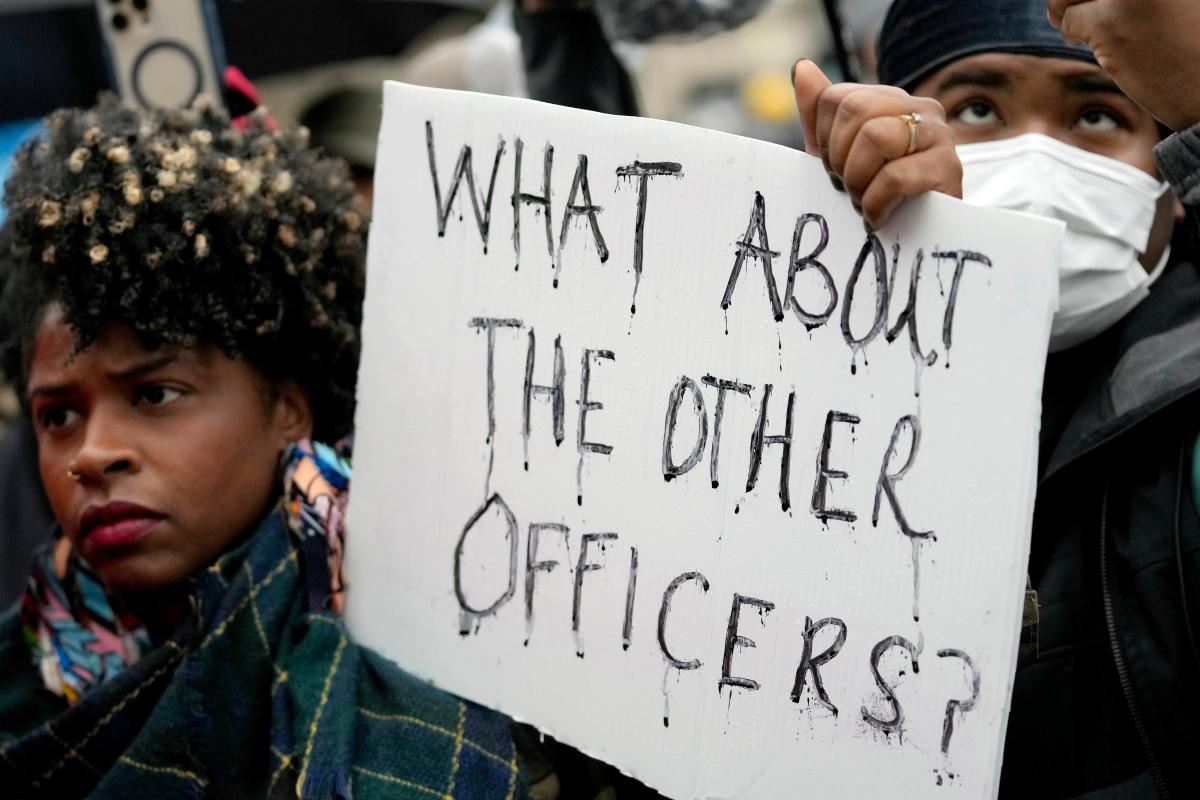

Now comes Memphis, where the Department of Justice announced Thursday a civil rights investigation into the city and its police force over alleged systemic use of excessive force and discrimination. The probe comes seven months after the beating death of Tyre Nichols by Memphis Police Officers following a traffic stop, in a case that sparked national outcry and calls for police reform.

Laurie Levenson, a professor at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles and former federal prosecutor, said an outside investigation and subsequent consent decree are critical for auditing police departments and enforcing change.

“The police cannot police themselves,” Levenson said.

Chuck Wexler, executive director of the Police Executive Research Forum, a Washington-based police research group, said a DOJ investigation is “not something they take lightly.” DOJ opens between 10 to 20 such cases annually among 18,000 police departments nationwide.

“It’s a major step, no question,” Wexler said. “The DOJ wants to take a look and see if Memphis’ practices, such as Tyre Nichols, is an isolated case or part of a broader series of patterns.”

DOJ probes US police departments over racism, violence

With Memphis, the DOJ now has open investigations into seven law enforcement agencies, including the Louisiana State Police, the New York City Police Department’s Special Victims Divisions and police departments in Phoenix; Mount Vernon, New York; Worcester, Massachusetts; and Oklahoma City.

The Justice Department has recently completed high-profile investigations in Louisville and Minneapolis, following the fatal shooting of Breonna Taylor and the murder of George Floyd, respectively. The DOJ is now negotiating consent decrees in those two cities to address the problems found from the investigations.

A consent decree is a federal court order. If a DOJ investigation finds problems in a law enforcement agency, it will enter into a legal agreement with that agency to essentially take over and enforce protocol for change. The decree could include updating current policies or creating new ones, revamping police training and establishing systems of accountability and transparency, according to the Baltimore Police.

Under the 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, the Justice Department’s civil rights division has the power to investigate systemic police misconduct.

The DOJ might launch an investigation for numerous reasons, including a community complaint, a high-profile case of police misconduct, or media scrutiny, according to Christy E. Lopez, a law professor at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., who led the Justice Department’s investigations in Ferguson, Missouri; Chicago and other cities.

If the DOJ finds a pattern of misconduct, it negotiates an agreement for reform — typically a consent decree overseen by a federal court and an independent monitor, said Danny Murphy, a police reform consultant and a former Baltimore police deputy commissioner.

Use of consent decrees varies depending on who’s POTUS

The push for consent decrees under the Biden administration marks a major departure from the Trump administration, which curbed the use of federal consent decrees to address police misconduct after then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions said the agreements made it difficult for police agencies to do their job.

Meanwhile, the Obama administration saw a record use of more than consent decrees to push for change in police departments in cities across the country including Baltimore, Cleveland and Seattle.

The use of consent decrees could change if President Joe Biden isn’t re-elected as president next year, said prominent civil rights attorney John Burris who represented Rodney King in the 1990s in Los Angeles, as well as Oscar Grant, who was killed by a transit police officer in Oakland, California, nearly 20 years later.

“With Memphis, the Justice Department has a very tight timeframe if it decides to use a consent decree after its investigation,” said Burris, who is based in Oakland. “A new administration can come in and put a halt to it.”

‘Not a perfect solution’

The investigation in Memphis could take up to a year and could result in a consent decree that would force many changes on a department that has long faced tension between its officers and the community, experts said. Still, sweeping and long-term reforms are expected to remain a challenge.

“I’m actually surprised it took so long for this type of investigation to take place there,” said Michael Alcazar, a retired New York Police Department detective and adjunct lecturer at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City. “It seems like there may be a lot of wrongdoing in Memphis and they don’t have enough checks and balances in place.”

Consent decrees can last up to a decade, or even longer, said Levenson, of Loyola. While an effective tool, Levenson said an agency can relapse after a consent decree is resolved because of systemic issues.

“These problems are so entrenched,” she said. “It’s not a perfect solution, but it’s probably the best tool we have.”

In Ferguson, which became an epicenter for police reform after mass protests following the fatal police shooting of Michael Brown in 2014, there were major changes eight years later.

Ferguson monitor Natashia Tidwell reportedly cited significant progress in officer training and community policing. The mostly all-white police department is more racially diverse. Traffic stops are less frequent and systems have been set up to hear resident complaints.

In Detroit, the police department rose from a consent decree in 2016 after 13 years under federal oversight. Changes included fewer officer-involved shootings, department-wide audits and “intensive inspections of police practices from the precinct to the command levels,” according to court documents.

Use of force expert says Memphis police unit ‘running wild’

Memphis police needs oversight, said Timothy Williams, a police use-of-force expert who served with the Los Angeles Police Department when it was under a consent decree from 2001 to 2013.

Williams said a probe into Memphis is sorely needed based on its high number of arrests from minor traffic stops and officers’ actions in the so-called SCORPION unit, which was billed as a violent crime-fighting unit. The five officers who have been charged with murder in Nichols’ death were all part of that elite unit.

“The arrests tell you there is no constitutional policing going on,” Williams said. “Their unit is running wild.”

Williams said federal monitoring of the LAPD led to better oversight and a tighter chain of command. A 2021 USA TODAY/Suffolk University Poll of Los Angeles residents, however, found the LAPD still uses force when it’s not necessary, and a third of those surveyed call the department largely racist.

For lasting change, Williams said Memphis will have to reevaluate its leadership as well as the officers it hires.

“If you want to change systemic issues,” Williams said. “You’ve got to change what comes into the organizations.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: DOJ probe of Memphis police has some experts asking what took so long?