Rachel Goldberg-Polin now lives by a new calendar – not weeks, or months, but days of absence and anguish.

Every morning when she wakes, she writes a number on a piece of tape and sticks it to her clothing. It’s the number of days since her son Hersh was taken hostage – she says stolen – by Hamas.

When we meet in Jerusalem that number is 155.

On the morning of 7 October, she turned on her phone to find two messages from Hersh. The first said: “I love you.” The second sent immediately afterwards read: “I’m sorry.” She called – no answer.

“It rang and rang,” she says.

“I wrote ‘Are you okay? Let me know you are okay.’ None of those (messages) were ever seen. My throat clenched and my stomach curled up. I just knew something horrible was unfolding, and I knew he knew.”

Hersh was caught up in the carnage unleashed by Hamas at the Supernova music festival. He sought refuge in a packed bomb shelter. Hamas militants were just outside, throwing in hand grenades.

The last image of the 23-year-old is in a Hamas video. He is being loaded onto a pickup truck, surrounded by gunmen. His left arm has been blown off.

The Hamas attacks killed around 1,200 Israelis, most of them civilians. Since then, Israel has bombed Gaza relentlessly, killing more than 31,000 people according to officials in the Hamas-run territory. 70% of the dead there are women and children.

While the war rages in Gaza, Rachel’s battle is to bring home her son, and the other hostages.

Hersh is among 130 hostages from the 7 October attacks remaining in Gaza. Israel believes at least 30 of them are already dead.

“Every morning I make a concerted effort and say to myself, ‘now, pretend to be human so that I can get up and try to save Hersh and the other remaining hostages’,” she tells me. “What I want to do is lay in a ball on the floor weeping, but that won’t help them.”

Rachel – a mother of three – is small and slight but she is a powerhouse. We meet at her family’s campaign headquarters – the office of a venture capital company, lent by a friend. Campaigning is now her full-time job. She hasn’t been back to work since the day of the attacks. Neither has her husband Jon.

But five months on, the focus on the hostages is fading – at home and abroad. Relatives are having to fight hard to keep them in the public eye.

Ask about her Hersh, and a smile lights up her face. “That’s my favourite subject – my children,” she says. “Hersh is a happy-go-lucky, laid-back soccer fan. He’s wild about music festivals and he has been obsessed with geography and travel since he’s been a little boy. “

Her son, who is an American-Israeli dual citizen, was due to leave for a round-the-world trip lasting a year or two. His ticket was already bought. The departure date was 27 December.

Hopes were raised of a deal to get the hostages back before the Muslim holy month of Ramadan – in return for a ceasefire of about 40 days and the release of Palestinian prisoners. A bleak Ramadan has come, without a breakthrough. But talks on a possible agreement are due to resume in Doha in the next day or so.

Rachel says she is always worried, scared, and doubtful – “You know the saying, don’t count your chickens before they hatch? I feel like don’t count your hostage until you’re hugging them.”

But hope, she says, “is mandatory”.

“I believe it and I have to believe it, that he will come back to us.”

In the midst of her torment, she is quick to acknowledge the pain of families in Gaza.

She says the agony must end, and not only for Israelis.

“There are thousands and thousands of innocent civilians in Gaza who are suffering,” she says. “There is so much suffering to go around. And I would love for our leaders, all of them, to say, ‘we’re going to do what we have to do so that just the normal people can stop suffering’.”

Experts say it’s not just the hostage families who are trapped in an anguishing wait. It’s also the 105 hostages who were freed in November during a week-long truce, leaving others behind.

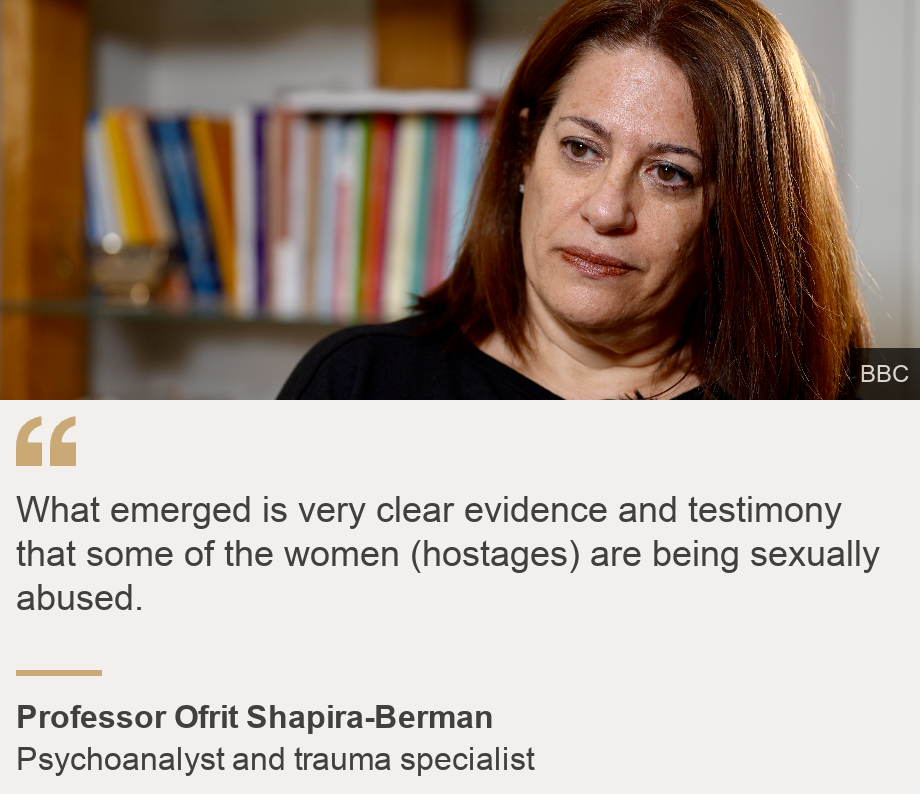

“Many of them keep telling us that they can’t even start grieving or healing until their friends or family members will be back,” says Professor Ofrit Shapira-Berman, a veteran psychoanalyst, and specialist in treating complex trauma.

“Many still have a relative in Gaza,” she tells us. “Others have friends they made during captivity. Everyone is waiting. That’s one thing they have in common. Their trauma is being delayed.”

On the morning of 7 October, Professor Shapira-Berman was already mobilising a volunteer network of physicians and mental health experts to provide support for survivors. Since November, they have also been treating returned hostages.

In her book-filled office in a suburb of Tel Aviv she gives us a painstaking account of what the hostages endured. All were psychologically abused, she says, but not all were physically abused.

“Some of them were beaten,” she says, “including the children. They were all given a very little amount of food, almost on the edge of starvation, very little water and sometimes water which was dirty. They were drugged. They were forced to take ketamine (used for anaesthesia). They were touched without consent, the whole variety,” she says, her voice trailing away.

There is particular concern in Israel for the women being held – with reason, she says.

“What emerged is very clear evidence and testimony that some of the women are being sexually abused,” she tells us, “not have been but are still being sexually abused”.

She is measured about what the future may hold for those who have been freed. At least some of them “will be able to love and to trust someone”, she says, but it may take years.

She warns that healing will be more difficult for those who were physically abused or came back to discover loved ones had been slaughtered and their home destroyed.

For those who remain in Gaza, five months on, she tells us, recovery is far less certain, even if they are ultimately freed. At best, it will take years.

And if they are not released, what does that mean for the hostages who have returned?

“Well, apparently your heart can break into endless pieces,” Prof Shapira-Berman replies. “So even though it’s broken already, it will be broken again. It’s like beyond my imagination that there will be no ceasefire. Even and when the hostages are back, this is our modern Holocaust. “

Family photos of Itai Svirsky show a dark-haired man with smiling eyes and full cheeks.

In one picture, the 38-year-old is strumming a guitar. In another he sits on a bench with his arm around his grandmother, Aviva.

In a propaganda video released by Hamas in January, there is a very different Itai – with sunken cheeks, bleary eyes, and a low voice.

He won’t be coming home. All his family can hope for is to get his body back from Gaza for burial.

They say Itai was killed by his guard – after an IDF air strike nearby – based on an investigation by the army.

“Itai was executed two days after by the terrorist that guarded him,” says his cousin, Naama Weinberg.

“We know he shot him. What would bring that man to shoot him after 99 days? It’s devastating. The disappointment is unimaginable. “

The army has denied Hamas claims that Svirsky was killed in the air strike, though it admits another hostage held with him probably was.

We first met Naama last November when she was campaigning for Itai’s release, and still had hope. Despite her loss she’s still campaigning – for the other hostages – though she is now wrapped in grief.

We caught up with her on a recent march by the hostage families from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem.

“I’m angry and I am sad because Itai will not come back anymore,” she says. “They (the government) did not do whatever they can, and they are still not doing whatever they can. Obviously, Hamas is not the best partner to negotiate with, but we want them back, and we want them back alive.”

Naama is pained by what Itai went through in his final months – witnessing the killing of his mother, Orit – a peace activist – on 7 October, and then languishing in captivity. And she’s pained by a sense that Israel is getting used to the hostage crisis.

“I’m very worried about it,” she tells me. “I am worried about the nature of humankind to accept situations. I am disappointed from Israeli society. I am disappointed from the whole world that is sitting quiet and letting this happen.”

Then she leaves us to rejoin the marchers on the road to Jerusalem.

Days later, relatives gather on the roadway at dusk – forming a tight circle of loss – and bringing traffic to a standstill outside Israel’s defence ministry in Tel Aviv.

Most carry posters with photos of sons, or daughters, or parents they have not seen or held since 7 October, when Hamas dragged them into Gaza.

Then comes a sombre count (in Hebrew) “one, two, three” and onwards – a tally of the number of days their loved ones have been gone.

That number is now 163 (as of 17 March).

Each word from the loudhailer resounds like an accusation directed at Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Signs read “Deal refusal = Hostages’ death sentence”.

Among the protesters we meet Amit Shem Tov, who wants his brother Omer back. He was taken from the music festival like Hersh Goldberg-Polin.

“As beautiful as he is from the outside, he is more beautiful from the inside,” Amit says, smiling at his brother’s bearded face in the poster by his side, “such a personality, too many friends, always making jokes, always laughs, always loves to dance, to live life. That’s him”.

Then the counting comes to an end, the few dozen protesters clear the road, and the traffic moves on – something the families of the hostages cannot do.

“For us, it’s still 7 October,” says Amit.