Across most of the battleground states, President Joe Biden’s reelection campaign is trailed by worrisome polling, gripes about a slow ramp-up and Democratic calls to show more urgency to the threat posed by former President Donald Trump.

Then there is Wisconsin.

Biden — who is scheduled to travel to Milwaukee on Wednesday to visit his state campaign headquarters — did not have to rev up a reelection apparatus in Wisconsin. Local Democrats never shut down a vaunted organizing network they built for the 2020 presidential campaign and maintained through the 2022 midterm elections and a 2023 state Supreme Court contest that was the most expensive judicial race in U.S. history.

Sign up for The Morning newsletter from the New York Times

While in other presidential battlegrounds, Democrats are still trying to explain the stakes of the 2024 election and what a second Trump term would mean, Wisconsin Democrats say their voters don’t need to be told the difference between winning and losing.

Democrats in Wisconsin spent eight years boxed out of power by Gov. Scott Walker and Republicans who held an iron grip on the state government, then four more with a gerrymandered Republican-led Legislature. Then they watched abortion become illegal overnight when a prohibition written in 1849 suddenly became law with the fall of Roe v. Wade. Party leaders in the state say there is a widespread understanding that the stakes are not theoretical.

“We organize year-round in Wisconsin,” said Lt. Gov. Sara Rodriguez. “We already have the infrastructure in place. We know how to do this, and we’ve been able to activate the folks who know what’s on the line.”

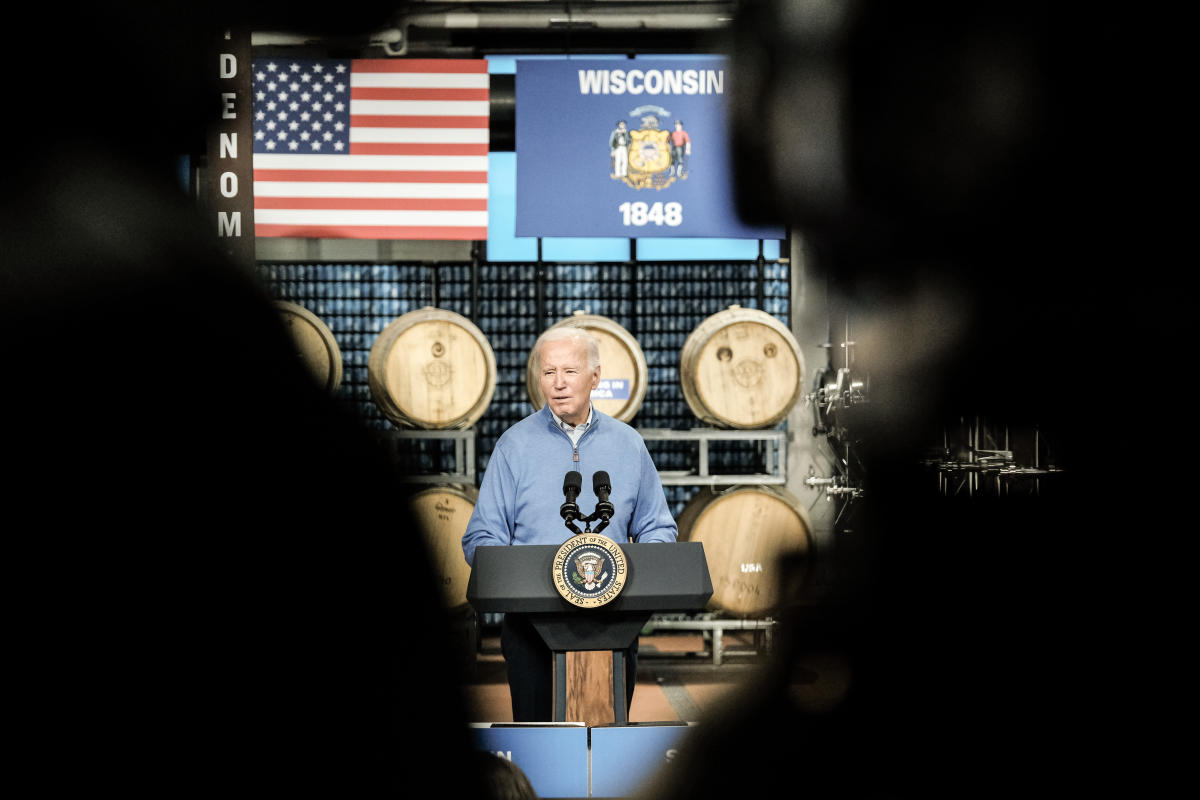

Biden has come to Wisconsin so many times — eight visits since he became president, and six for Vice President Kamala Harris — that for many Wisconsin Democrats, his visit Wednesday comes almost as an afterthought.

Just as big a deal for local organizers, Rodriguez said, are the Democratic Party of Wisconsin’s canvass kickoff events, which are set to begin Saturday at the 44 offices opened by the party and the Biden campaign throughout the state. Rodriguez said she was planning to be at one in Wausau, a central Wisconsin city where the progressive mayor is up for reelection in April.

It helps Biden that the two issues his campaign has placed at the heart of his campaign — abortion rights and democracy — have been at the center of Wisconsin’s political discussion in recent years.

Polling from The New York Times and Siena College in November found that while Biden had an advantage of 3 percentage points on the question of democracy across all of the top battleground states, he had a 13-point lead on the issue in Wisconsin alone. In those polls, Biden led in Wisconsin while trailing in each of the other battleground states.

More recent surveys from Marquette Law School and Fox News have found Biden and Trump effectively tied in a head-to-head contest; with third-party candidates included, Trump edges ahead by 2 or 3 points.

Republicans in Wisconsin contested Biden’s 2020 victory there, which came by just 20,608 votes, well into 2022. One of the party’s candidates for governor in 2022 ran on a platform of decertifying the 2020 election and rescinding Wisconsin’s 10 electoral votes (which is not something the Constitution allows), and the state Assembly authorized a yearlong, $2 million investigation into election fraud that turned up no new evidence.

Last year, a liberal candidate, Janet Protasiewicz, won the crucial state Supreme Court election in a major victory for Democrats. Soon after, Robin Vos, the powerful Republican speaker of the state Assembly, floated the idea of impeaching her before she could cast deciding votes on cases that would eventually lead to overturning the state’s gerrymandered legislative maps and its abortion prohibition.

Internal polling by the Democratic Party of Wisconsin in September found that 70% of Democratic voters had heard about the Republican impeachment threats — an extraordinary figure considering it was a state issue in an era of weakened local news reporting.

And right-wing Wisconsin Republicans remain angry. On Monday, a group of them submitted more than 10,000 signatures to recall Vos, who despite his efforts to sow doubts about elections is widely viewed as being insufficiently loyal to Trump. (The Wisconsin Election Commission said on Tuesday that an initial review had found that the recall group’s petitions did not contain enough valid signatures to force a recall election for Vos.)

Sen. Ron Johnson, the spiritual leader of Wisconsin Republicans, said in an interview Monday that Biden’s standing in the state depended more on voters’ sour views about the economy than on questions about democracy and abortion rights.

“When you go to the grocery store and you take a look at what the bill is, when young people try and buy a house and realize it’s completely unaffordable, when you’re stuck in your house with your low-interest-rate mortgage and you can’t trade up because interest rates are so much higher, these are the things that actually impact people,” Johnson said. “They’re not economists. They’re not looking at the monthly economic figures that Biden tries to tout.”

Johnson said that he was “hoping Democrats won’t be able to scaremonger” on abortion rights and that he did not believe Wisconsin Republicans’ efforts to question the validity of the 2020 election — some of which he was involved in — would have ramifications for 2024.

“I think those are pretty well-forgotten stories, personally,” he said. “The 2020 election mess is pretty well in the rearview mirror.”

Whether that’s true or not will become clearer at the Republican National Convention, to be held at Milwaukee’s professional basketball arena in July.

Abortion is also a far more tangible issue in Wisconsin than in the other political battlegrounds.

The procedure became illegal overnight in 2022 when the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade and the state’s 1849 law kicked in. Women across the state were enraged, and the issue powered victories for Gov. Tony Evers, Protasiewicz and several mayors last spring.

By the time courts ruled in September that abortions could resume in the state, Evers and other Democrats had carried out a 15-month campaign to remind voters that conservatives were responsible for the ban. When he won his bid for reelection to the Senate in 2022, Johnson campaigned on holding a statewide referendum on the issue — in part to deflect his party’s support for abortion restrictions.

Dianne Hesselbein, the Democratic minority leader in the state Senate, said abortion politics were still driving political discussions — including one at her birthday party this past weekend.

“My 24-year-old daughter was saying how excited she was to vote for Biden and how she never thought that this whole thing with abortion would really happen,” Hesselbein said.

One spot of danger for Wisconsin Democrats is the slow decline in turnout and enthusiasm from the state’s Black voters, many of whom live on Milwaukee’s north side. In January, a Republican member of the Wisconsin Election Commission wrote in an email to party members that a decline in the city’s Black turnout was “due to a ‘well thought out multifaceted plan.’”

Democrats, who have fought for years with little success against Republican efforts to require voter identification, limit drop boxes and enact other restrictions on voting, said in interviews that the elections of Black Democrats as the Milwaukee mayor and the Milwaukee County executive would give Biden key party surrogates that he did not have in his 2020 campaign.

“That’s really going to help us bring that enthusiasm to these neighborhoods, to the communities that we grew up in,” said David Crowley, the county executive. “We can talk about the work that we have been able to do.”

c.2024 The New York Times Company